Does Xi Jinping understand seed investing and capital allocation?

Takeaways

- AngelList claims the optimal seed stage investing strategy is to index into every deal

- Capital allocation is fundamental to company growth but most people don’t know how to do it

- What do Michael Phelps and JK Rowling have in common?

Invest in all the (seed stage) things

AngelList released research claiming that “seed stage investors would increase their expected return by broadly indexing into every credible deal, a finding that does not hold at later stages.” If true, this implies early stage VCs don’t add value, which might trigger half my readership base be worth looking into.

AngelList is naturally biased since they have their own venture investing product, but let’s take a closer look [1]:

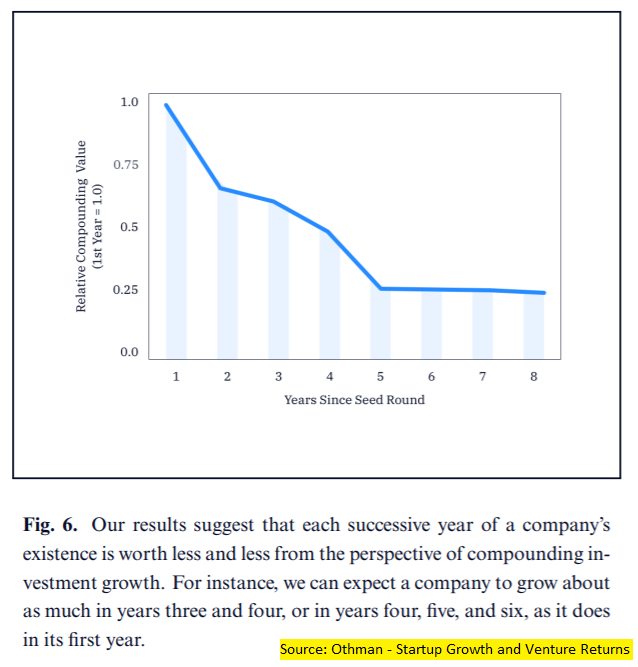

we rely on two concepts. The first is that startups tend to grow faster in their earliest years […] The second is that early-stage investments have longer durations than later-stage investments in those same companies, which is tautological.

Taken together, the two concepts imply that winning early-stage investments have more years to compound at higher rates of growth.

Growth rates tend to slow once you scale, so the first concept makes sense. It’s harder to do 10% growth on $1bn vs $1000, as anyone from the Chinese government to Facebook would remind us when issuing financial guidance.

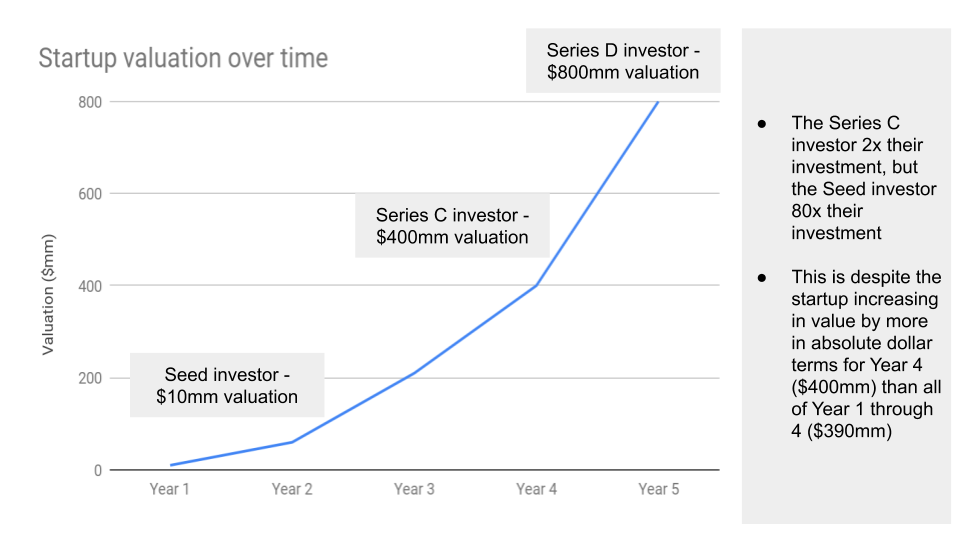

I was confused by the duration concept at first, thinking AngelList meant that the average time between fundraising rounds increases as you get later stage, which is not an obvious conclusion [2]. This wasn’t what they meant though; they’re simply saying that an early-stage investment is earlier than a later-stage investment in that company. If you invested in the seed round, you’ve had longer and higher growth rates to compound your money at compared to investing in the Series C.

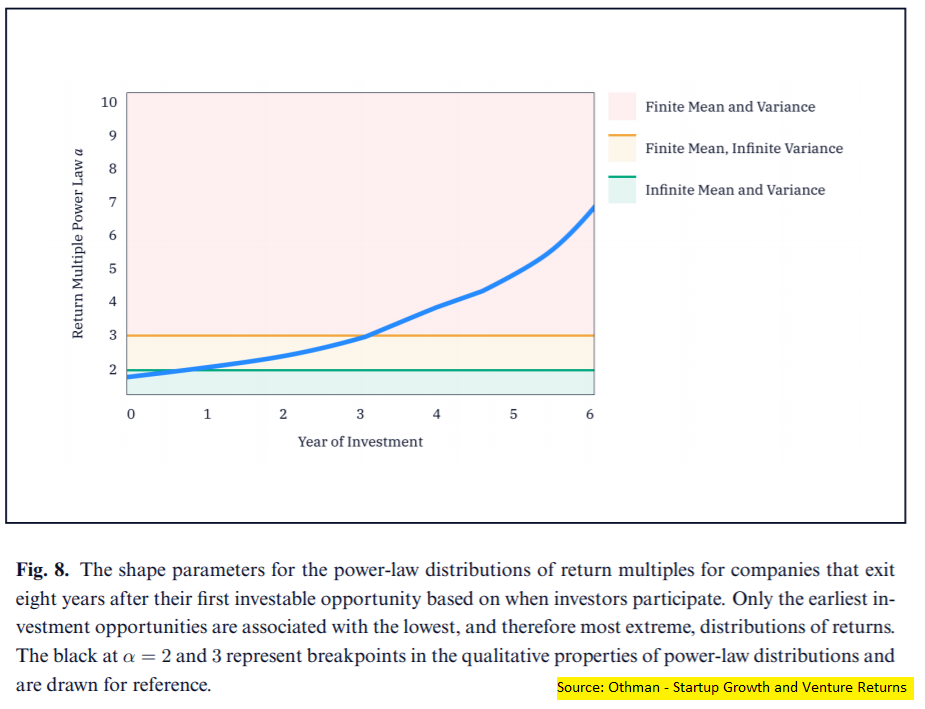

after five years a winning seed-stage investment begins to draw its return multiple distribution from an α < 2 (i.e., unbounded mean) power law. This means that the regret an investor could have for missing a winning seed-stage investment is theoretically infinite

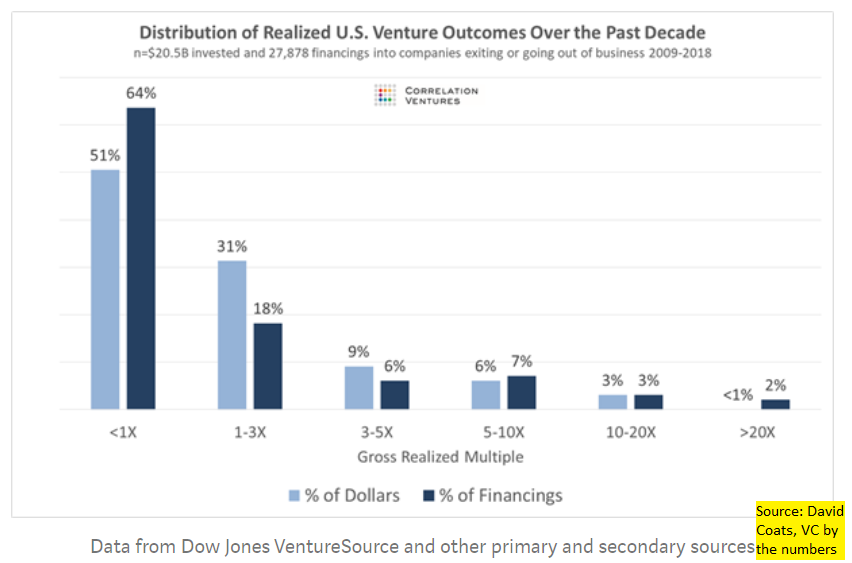

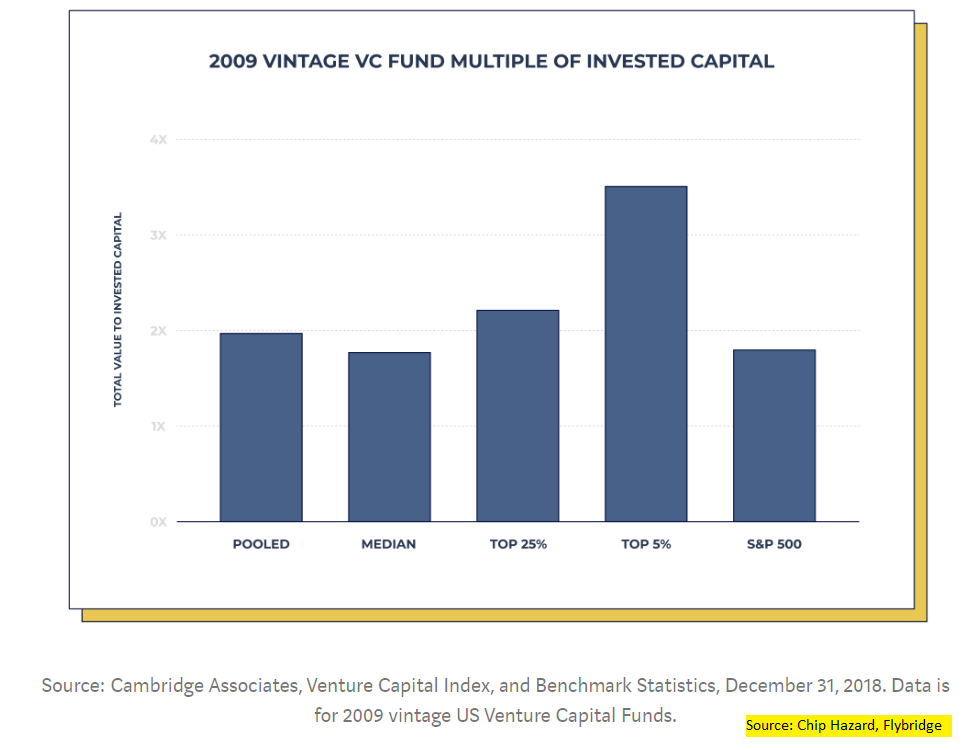

Venture returns tend to follow a power law distribution rather than a normal distribution, implying that outlier extreme values are a feature rather than an exception. See here for more info on power laws.

This applies both for company returns:

As well as returns of the VC firms:

There are different types of power laws [3], and AngelList is claiming that early-stage venture returns follow a particular kind that implies infinite return and variance. Missing out on any single seed investment that then wildly succeeds would lead you to have theoretically unlimited loss.

investors in different rounds of fundraising experience different distributions of expected returns

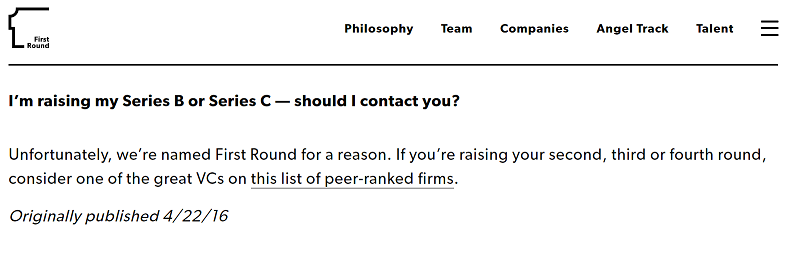

these distributions change so much over a startup’s lifetime that early- and late-stage venture capital should be treated as distinct asset classes

Given how private investors already differentiate themselves based on what stage they invest in, this sounds reasonable. For example:

AngelList filters their dataset based on the following criteria:

three filters of (1) winning syndicates that (2) have had at least one year to season (or have exited) and (3) for which we know the date of the seed round, leaves us with a database of 684 non-negative investments, constituting 487 initial seed investments and 197 later follow-on investments into those the same companies

Filters 2 and 3 make sense on first glance, since we want to exclude anomalous or incomplete data. We’ll come back to filter 1 shortly.

What follows then is a bunch of math that I won’t get into during the holidays [4], which concludes that

1) company growth rates fall over time

2) the most extreme power law distributions apply only to early stage investments, year one or earlier

In other words, you want to get in as early in companies as possible, and the more you can get in the better.

“Well, of course if you restrict yourself to just winning investments, you’ll get this conclusion”. The report responds to this by claiming:

as long as a constant fraction of investments lose money, money-losing investments will only affect the quantitative, rather than qualitative, properties of the investment class

If you’re adding negative 100% individual returns to a distribution that has infinite mean and variance, it affects your final return but not the shape of the distribution itself. Theoretically you should still get in as many companies as you can.

However, we do not feel that investing in everything is practical […] Consequently, our results suggest that at the seed stage investors should put money into every investment that clears some minimum threshold

This is the most problematic part of the paper for me [5]. We’ve just concluded that we should invest in as many companies as we can, but now have to subject them to an arbitrary filter. AngelList suggests something like “Is there a version of this company that could raise a Series A from a VC?” This implies subjective judgement is still required, and that you can’t just index into every seed stage deal you see. Perhaps early stage VCs are doing something other than arguing about minimum working hours after all

which seems to require subjective judgement, leading us back to inferring that VCs do have value add on the investment process after all. If there is some threshold to be met, I’d assume some people are better at defining and analysing that threshold than others, and should be compensated accordingly.

It’s plausible that indexing in seed stage investing is the optimal strategy, just as indexing in public market investing is ideal for the average person. Jack Bogle was laughed at during the creation of Vanguard; indexing seed stage investments seems a laughable idea now but could follow the same path. Until there is more work done on how to create that threshold though, I have 25% certainty that seed stage index investing affects the returns of established VC firms in the next 3 years.

How do we get better at capital allocation?

There’s been increased focus on how management spends money lately, with books such as The Outsiders giving case studies of top capital allocators. Michael Mauboussin, Dan Callahan, and Darius Majd put together a comprehensive document on capital allocation here that is worth reading in entirety. Highlights below:

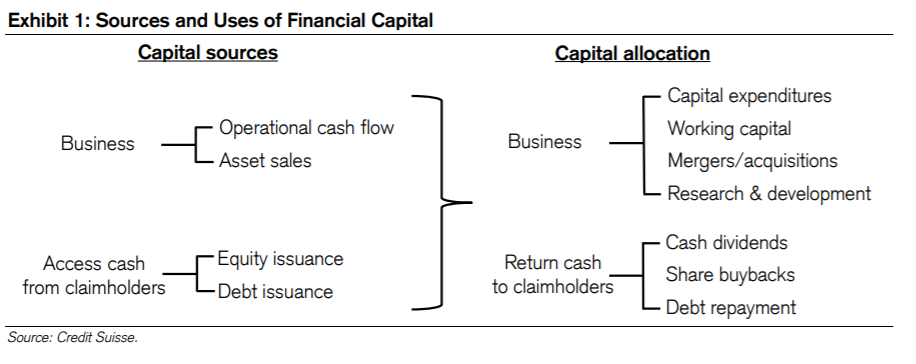

Capital allocation is the most fundamental responsibility of a senior management team of a public corporation. The problem is that many CEOs […] don’t know how to allocate capital effectively.

The proper goal of capital allocation is to build long-term value per share. The emphasis is on building value and letting the stock market reflect that value. Companies that dwell on boosting their short-term stock price frequently make decisions that are at odds with building value.

How do we differentiate from management building long term value vs pumping short term stock price for their next yacht? It’s difficult, but they provide some guidelines later in the document. First, we need to understand how companies get their capital and how they use their capital.

Possible sources of capital (how a company gets money) and allocation of capital (how a company spends money) include:

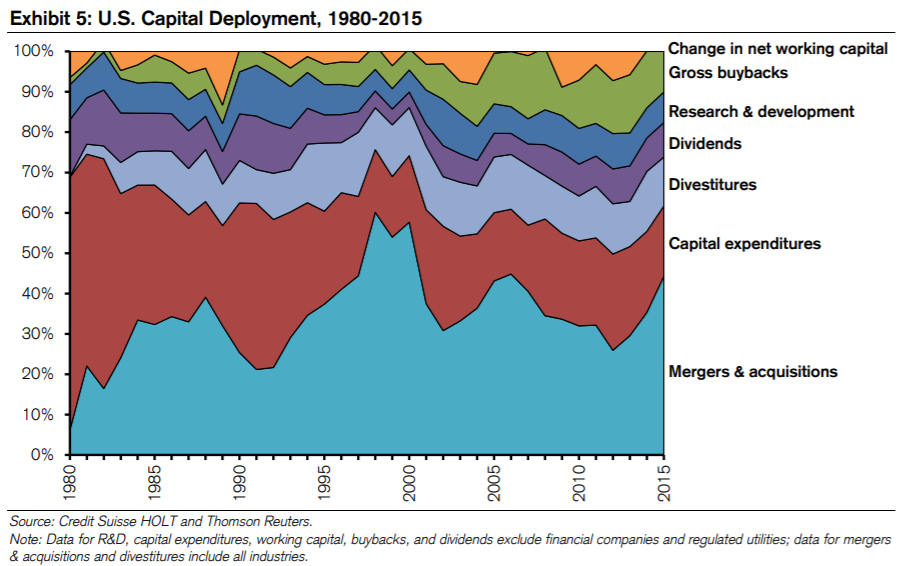

How has this changed over time?

Takeaways from the above:

- M&A is cyclical with the economy

- Capex declined, possibly due to the shift in industry mix

- Buybacks increased significantly after a change in regulation

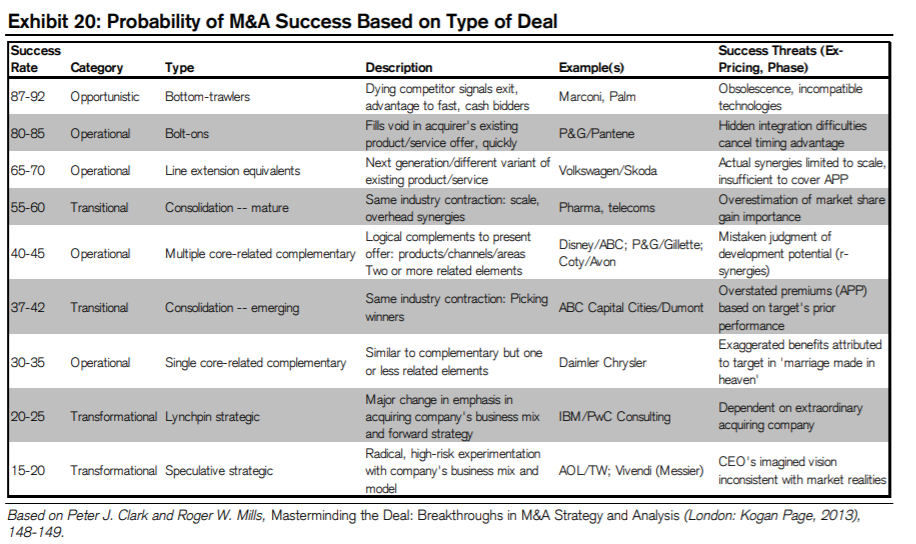

How should we evaluate M&A? The paper cites other research on different types of M&A having different success rates:

For example, deals they call “opportunistic,” where a weak competitor sells out, succeed at a rate of around 90 percent.

“Operational” deals, or cases where there are strong operational overlaps, also have an above average chance of success.

The rate of success varies widely for “transitional” deals, which tend to build market share, as the premiums buyers must pay to close those deals can be prohibitive.

Finally, the success rate of “transformational” deals, large leaps into different industries, tends to be very low.

On capex, the paper claims:

Companies that invest in industries with a high return on invested capital and good growth prospects are more likely to create value. The cyclicality of the industry is another important consideration in assessing capital expenditures […] companies spend when things look good and hunker down when they don’t.

And for the other categories:

- R&D value creation is ambiguous and difficult to measure [6]

- A lower cash conversion cycle (better management of net working capital) is correlated with a higher return on capital [7]

- Divestitures are substantial and generally create value

- Dividends must be reinvested to get the full rate of return; most are not [8]

- Stock buyback returns depend on valuation [9]

Companies buy back stock or issue dividends as ways to return cash to shareholders. The merits of both of these are still debated. Barry Ritholtz dislikes buybacks; Cliff Asness thinks the negatives are overstated. Retirees like dividends; Meb Faber doesn’t. The paper discusses some of these points as well.

Ultimately, the answer to all capital allocation questions is, “It depends.”

Having read skimmed the above, how should we put this in practice? The paper ends by building on research by others to get a few guidelines of capital allocation:

- Zero-based capital allocation. Companies generally think about capital allocation on an incremental basis. The proper approach is zero-based, which simply asks, “What is the right amount of capital […] in order to support the strategy that will create the most wealth?”

- Fund strategies, not projects. The idea here is that capital allocation is not about assessing and approving projects, but rather assessing and approving strategies and determining the projects that support the strategies

- No capital rationing. The attitude at many companies, which the results of surveys support, is that capital is “scarce but free.” A better mindset is that capital is plentiful but expensive

- Zero tolerance for bad growth. Seeing an investment flop is no sin; indeed it is essential to the process of creating value. What is a sin is remaining committed to a strategy that has no prospects to create value

- Know the value of assets, and be ready to take action to create value. Intelligent capital allocation is similar to managing a portfolio of stocks in that it is very useful to have a sense of the difference, if any, between the value and price of each asset

Kindness

Many years ago, a friend invited me to thanksgiving dinner in his dorm. We weren’t super close, and I appreciated the invite since I wasn’t doing anything then, on account of being a broke international student. We had a fun small group dinner and I got to meet his other friends. It was a good time.

Three weeks later on Dec 17 my friend killed himself.

Once in a while I remember this happened.

I remember how mad I felt.

Then how sad.

And I remember him.

Every December I write about this to remind myself and others to get some perspective. There are things more important than VC returns and capital allocation. Suicide is still stigmatised; depression downplayed.

Think only losers get depression? Here are some highly successful people:

Know what else they have in common? They’ve all suffered from depression. Yes, even some of the greatest olympians and best-selling authors were depressed. If you are depressed, know that you are not alone. It is not your fault.

If you are depressed and feeling suicidal, please reach out for help. Close friends or family might not realise what you are going through if you don’t tell them.

Don’t want to talk to your friends? The suicide hotline is 1-800-273-8255 [10]

Don’t even want to talk on the phone? There’s a texting service, text 741 741 [10]

For the rest of us lucky enough to go through life without illness, know that some of your friends may be secretly suffering. Look out for them, and be there for them. Depression is a real illness, not just something ‘to get over’. People aren’t blamed for falling sick; neither should they be blamed for becoming depressed. This talk is helpful for getting some understanding of what depression is like.

As we head out of the holiday season and into the new decade, let’s try to be just a little bit more kind. A little bit can go a long way.

In memory of Hunter Smith

Shout outs

As always, happy to meet anyone in person; replying to this goes directly to my email

- Benton Moss is putting together a collection of the best business content, feel free to reach out if you’d like to contribute.

- Brian Kaplowitz co-founded PB&J, a product development studio to strategise, design, and develop apps if your company needs that expertise. See here for a deck; feel free to reach out directly.

- Julian Weisser co-founded On Deck, “the first place top talent looks when thinking about starting or joining a startup”. Applications for their next cohort are open now

- Madeline Sullivan is looking for investors for her upcoming Manhattan restaurant with hospitality entrepreneur Eamon Rockey, the five-time Michelin-starred restaurateur responsible for Betony, Atera, Compose and Aska. See here for a deck; feel free to reach out directly.

Other

- What can the world’s oldest organisations tell us about designing organisations to last? Summary chart here

- A small experiment using chauffeurs to simulate autonomous vehicles resulted in a large increase in miles travelled [11]. The experiment has issues (low sample size, not being able to measure system efficiency gains etc) but something to think about

- Does online advertising work? I’m less skeptical than the article.

- “When in Russia, he peppers his speeches with the words of Dostoevsky and Golgol; when in France, of Molière and Maupassant. To better understand the meaning of The Old Man and the Sea, [he] traveled to Hemingway’s favorite bar in Havana.” The person in question is Xi Jinping; excerpt from this book review

- Notes from a recent investment conference a friend invited me to, which included speakers Cliff Asness, Michael Mauboussin, and Barbara Ann Walters.

Footnotes

- It has been a while since I’ve taken stats or econometrics, feel free to write in to correct any incorrect interpretations I made.

- Carta’s separate dataset here implies that median time between funding rounds increases. Crunchbase’s dataset here varies depending on stage.

- I don’t claim to understand all the math, but see here or here for more detail on the various possible combinations of first moments (mean) and second moments (variance) of distributions.

- Or ever, for that matter.

- Aside from the math, but that was a lost cause.

- “The academic research on the effectiveness of R&D spending is somewhat equivocal, in part because of the measurement challenges and the decline in R&D productivity in the pharmaceutical industry […] A reasonable question is whether the stock market effectively reflects R&D spending. One large study found that the market does it well.”

- “The cash conversion cycle (CCC), a calculation of how long it takes a company to collect on the sale of inventory, is the standard way to analyze working capital efficiency. The CCC equals days in sales outstanding (DSO) plus days in inventory outstanding (DIO) less days in payables outstanding (DPO) […] The impact [of CCC] on total shareholder returns, however, is less clear”

- “It’s crucial to acknowledge that almost no one earns the full TSR because most individuals do not reinvest the dividends they receive, and dividends are generally taxable. While there are no clear-cut data on the topic, it appears that only one-tenth of all dividend proceeds are reinvested”

- Buybacks were irrelevant in the U.S. until 1982 due to regulation. “First, if you are the shareholder of a company that is buying back stock, doing nothing is doing something. By choosing to hold the shares instead of selling a pro-rated amount, you are effectively increasing your percentage ownership in the company. Second, it is logical that you would prefer that the companies you hold in your portfolio buy back stock rather than pay a dividend. If you own shares of companies that you think are undervalued, buybacks will increase value per share by definition.”

- US only, see here for other country numbers

- Credit to Benton Moss