Fluctuat nec mergitur

Takeaways

- Design better rating systems using relative rankings, user behaviour, and response rates

- Financial crises are about liquidity and not capital

- The corona crisis will define a generation; choose how it defines you

Question of the month

If you have been affected by the crisis and think I could help, please reply directly to this email and we’ll problem solve together.

Designing a better marketplace feedback system

You use rating systems all the time: apps on mobile, drivers on uber, restaurants on google maps [1]. You’ve also probably noticed how most of them are flawed, not giving you enough precise information to decide if the thing is actually good. A 4.5 star rating doesn’t mean much when everyone is also above 4 stars. Josh Breinlinger of Jackson Square discusses why this happens to marketplaces here and proposes some solutions.

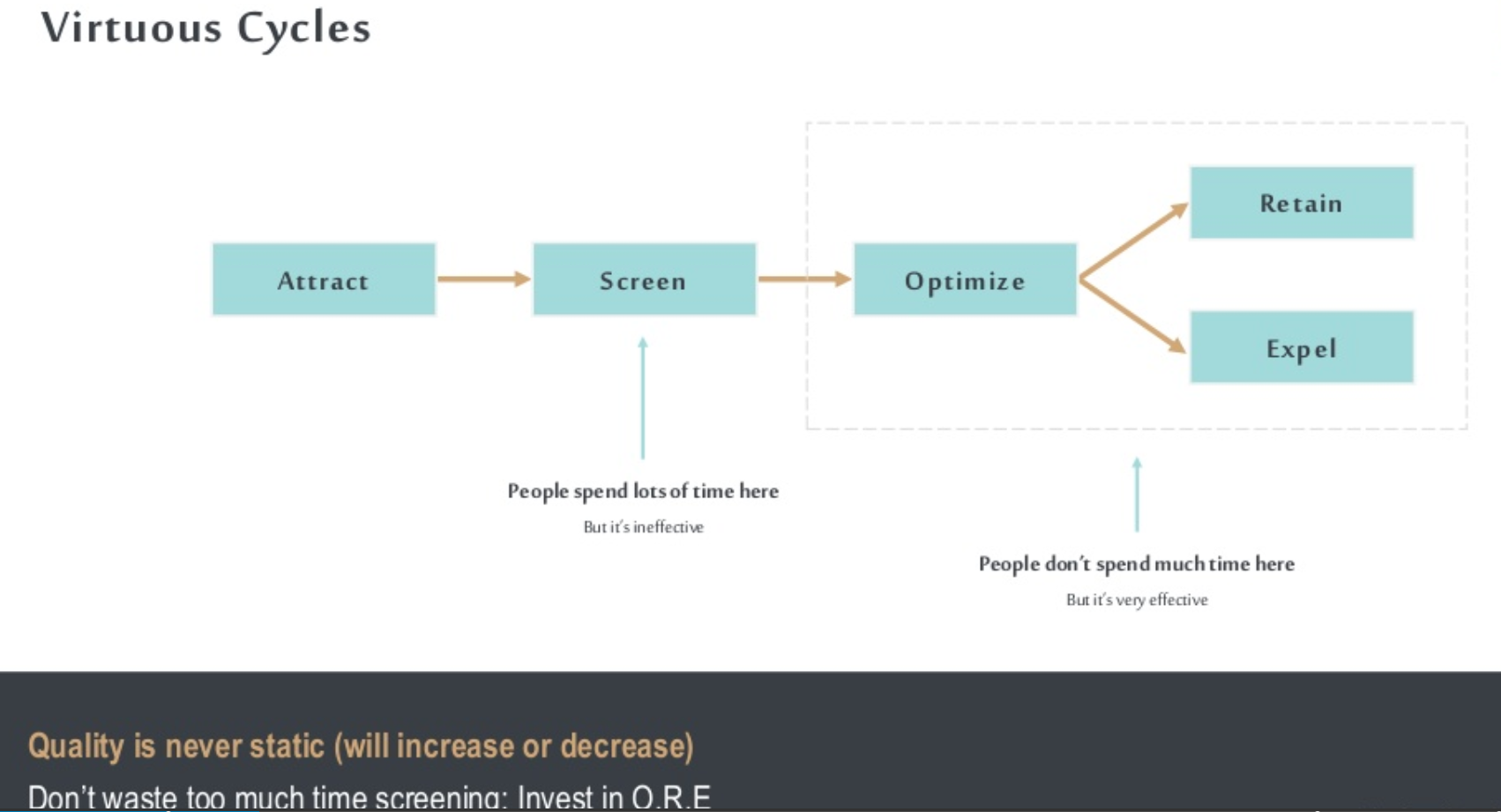

Ppl focus too much on screening initially, when they should focus on optimisation post acceptance

To make sure we’re on the same page, we’ll define a marketplace as a platform that matches buyers and sellers. Amazon, AirBnB, Upwork are all marketplaces.

Most marketplaces have some quality screening process at the start, and once you pass that you rarely get taken off the platform. Josh is saying that marketplaces should focus on the optimisation, retention, and expulsion processes more than the screening process, as these will be more effective in maintaining quality. It’s the difference between measuring potential vs actual service by the provider.

This makes sense, and the difficulty here is one of scale. If you run a screen and then don’t care about quality after, you only need to run it once for every new participant. If you invest in regular quality evaluations, you’ll have to run it multiple times, on a participant base that gets larger over time. The costs of doing the latter are likely to continue scaling with your growth as well, not something anyone wants to hear [2].

5 star ratings can separate bad sellers but don’t have enough granularity to separate good vs great

5 star systems give people a false sense of precision. Since people choose 5 as the default, “average” rating, differentiating between good vs great is close to impossible. You can get a sense of the terrible sellers, since a 1 star review pulls down the average dramatically [3], but the difference between a 4.7 vs a 4.5 is likely noise rather than signal. If you want to know the best sellers, and most people do, 5 star ratings aren’t that helpful.

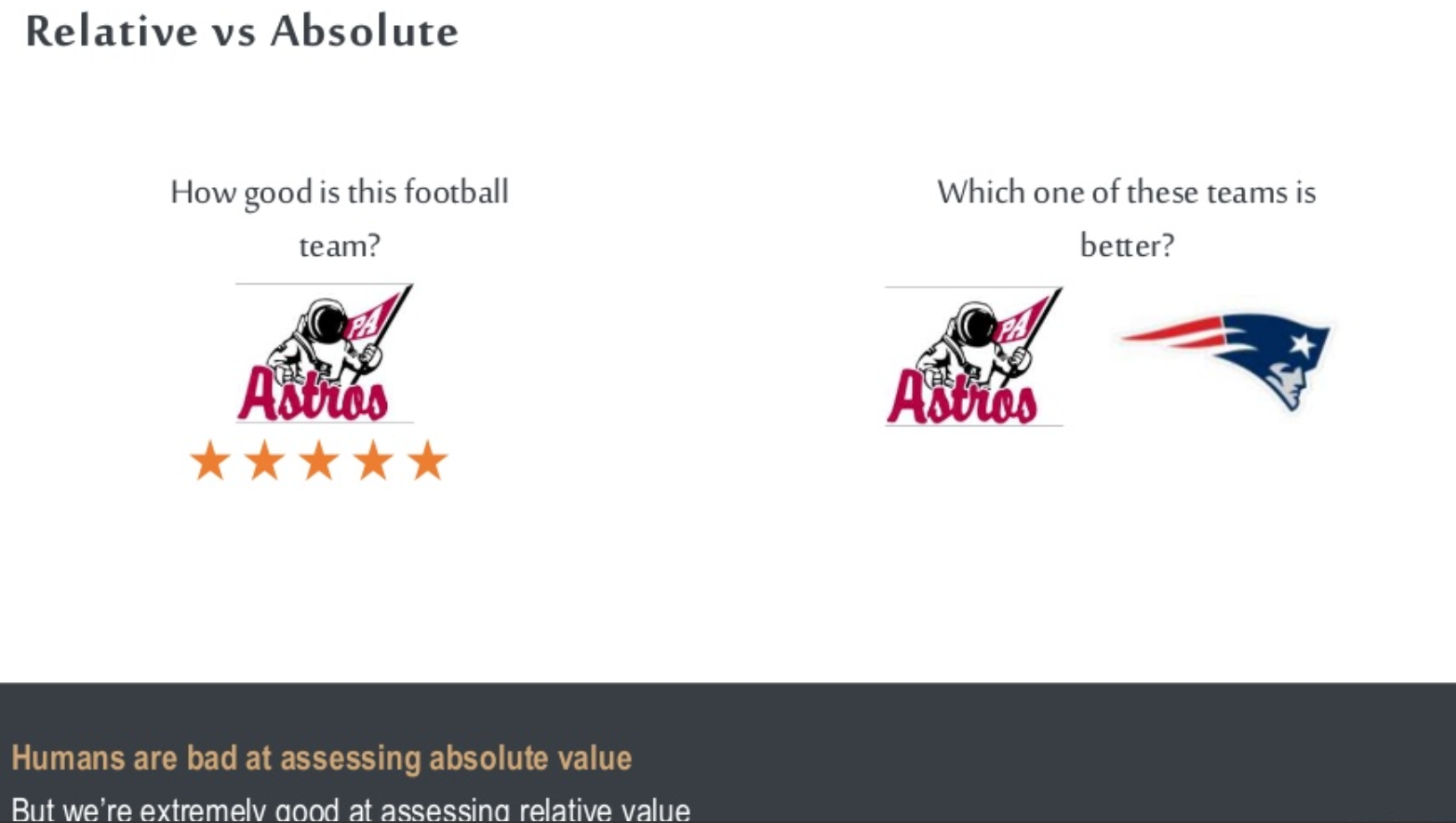

Even if the ratings start out effective, grade inflation over time leads to their irrelevance. The paper there shows how raters feel pressure to give “above average” ratings, continuously pushing the average higher. Think about how reviews for movies, liquor, games all cluster towards the higher end of the range [4]. We aren’t well calibrated to give ratings on an absolute basis.

Josh assumes a normal distribution of sellers. Are there cases when this doesn’t hold? I can’t think of many at the moment, outside of artificially restricted platforms where the selection process is exclusive rather than inclusive. For example, if you were to create a membership club for top restaurants, the sellers wouldn’t be normally distributed. This doesn’t affect the validity of the point though, and perhaps even supplements it, since you want even finer granularity between the top sellers.

A relative rating rather than an absolute will be better in separating the good from great

Josh gives the example of ELO ratings, most commonly used in chess, as a way to mitigate this review problem. ELO ratings compare the results of a competition between two players, awarding points for wins and deducting points for losses. By making ratings a result of comparing people relative to another, we’ll get better quality information of who is good and who is great.

Besides user feedback, Josh also suggests to use actual buyer behaviour as another signal of quality. If users are presented 3 different babysitting providers and consistently pick one, that provider should be given a better score. Sellers that are consistently closing sales will be seen more often.

This does create a problem where new entrants find it hard to break in. For example, Amazon’s first page of organic results usually returns the larger, longer tenured sellers. This is good for the marketplace in the short term since buyers can trust in the quality of the product. I’m less certain it’s good in the long term since it might hide new sellers that have better quality at a lower price, who never get enough traction to survive.

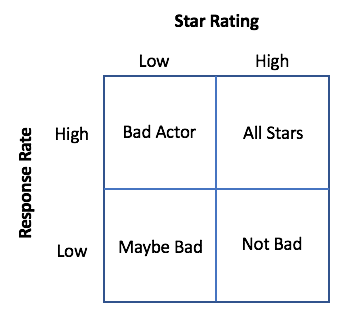

In a separate post, Josh talks about using response rate as a quality signal as well. All else equal, having a higher response rate in feedback means the feedback is better quality. A TV series that has 4 stars with a 100% response rate is better than a series that has 4 stars with a 10% response rate.

The idea behind this is whether users like the thing enough that they can overcome the initial hurdle of providing feedback. If they didn’t have a strong feeling on the subject, they wouldn’t bother rating. Ambivalence is bad; the opposite of love is not hate but being ignored.

The tricky part comes when one seller has a lower rating but higher response rate than another. You could make the argument that the higher response rate is a better indicator of quality, but you could also say that more people were motivated enough to give it a lower rating. It does depend on your marketplace, and perhaps you could arbitrarily define how much response rate converts into a point on ratings.

Josh also discusses pricing models of marketplaces, which you can check out in the slides linked. His main points there are that marketplaces should charge fees less than the efficiency gained, that there are three primary pricing models, and optics matter in who is paying fees. I’m not going to cover these in order to keep this section on topic.

If you’re building a marketplace, Josh’s points can be summarised as:

- evaluate actual rather than potential quality

- use relative rather than absolute ratings to get more granularity

- use other signals beyond user feedback scores, such as actual behaviour or response rate

Misunderstanding financial crises

I read “Misunderstanding financial crises” by Gary Gorton a few years back. It has good points on why financial crises occur, and could be rewritten to have more structure and clarity. Highlights below:

Financial crises all have the same root cause - bank runs and sharp reductions in demand for deposits in the banking system. Crises occur when market participants mistrust the value of bank debt, and there’s a sudden large demand for cash from the financial institution

Demand for cash is on such a scale it is not possible for the banks to meet this demand because assets cannot be sold en masse without prices plummeting

Crises have happened throughout history, are sudden and unpredictable

Banks are in the business of borrowing and lending money, both to consumers (retail) and companies. When you or your company deposits money into the bank, you’re giving the bank a loan with the expectation you’ll be able to withdraw that cash in the future. Banks in turn lend out more money than they have, in what’s known as fractional reserve banking, with the expectation that not everyone will want to withdraw at the same time. This allows the supply and velocity of money (credit) in the economy to increase and provides liquidity.

Consumer bank runs are largely a thing of a past, due to 1) FDIC deposit insurance and 2) the size of consumer deposits vs company deposits. It’s no longer like the 1920s where 2 banks would fail a day.

The bigger risk now is bank runs from institutions, be they companies or investment firms. In times of crisis, these firms want to get their cash back. When they all want it at the same time, it’s impossible for the banks to fulfil that demand.

I’ll skip over the nuances of how these companies keep their cash; if you’ve read about the terms repo, commercial paper, or revolving credit lately, those would fall under that umbrella. To simplify, banks have obligations to companies in a variety of forms, and companies are now calling on those obligations to get cash [5].

The main point here is that liquidity is the cause of crises, not capital. The bank could still have a lot of capital in the form of illiquid assets, but be unable to provide enough cash on demand at that moment. And the bank can’t even sell the less liquid assets at a good price, since it’s a crisis, resulting in a downward spiral of liquidity.

Markets are liquid when there is nothing to know or nothing worth knowing; when there aren’t secrets

Conversely, when there are too many unknowns, liquidity stops. In the 08 crisis, banks didn’t want to lend to each other because they didn’t know which other bank was insolvent. Now, people don’t know when normal business will resume, and which businesses will survive. That’s why the Fed is stepping in to try and increase liquidity and provide a known source of funds.

The banking system has always been viewed as too big to fail. No society has intentionally liquidated its banking system; instead they choose not to enforce debt contracts. They do so by

1) allowing suspension of convertibility (no withdrawals) or declaring bank holidays (total suspension of all bank services)

2) declaring banks not insolvent even if they do not pay their debt

3) bailouts of bad assets

Money and credit is critical to society as it stands currently, and has been for centuries now. It’s the inherent tradeoff in having fractional banking, since credit relies on trust. In good times when trust is high, liquidity isn’t a concern, credit is extended, and economic activity occurs. In bad times when trust is low, liquidity disappears, credit is withdrawn, and economic activity stalls [6].

Fluctuat nec mergitur

Goodness is not goodness that seeks advantage. Good is good in the final hour, in the deepest pit, without hope, without witness, without reward. Virtue is only virtue in extremis [7]

I can’t predict when this crisis will end. I hope it’s soon, though I fear it’s not.

What I can predict is that this crisis will show people for who they really are. Crises reveal the best but also the worst in us. There will be those that help and those that harm. Those that keep their word and those that break it. Those that make their reputation and those that disgrace it.

Choose which group you want to be. Choose wisely.

The city of Paris has a motto, Fluctuat nec mergitur, meaning “tossed by the waves, but does not sink”. I’d like to believe this applies to all of us. We’re in for a rocky time, but will weather this storm as we always have, by helping each other.

I have no doubt that we will pull through this. Bruised but not broken, we’ll recover having reassessed who and what matters most. And one day we’ll be telling stories of how we survived by coming together as a community [8].

I also have no doubt that these will sound like hollow platitudes if you’ve been personally affected by the crisis. In my biggest failures, I heard them all - time heals all wounds, failure is one step to success, losing opens up new opportunities. I instinctively knew them to be true, but honestly didn’t give a shit then.

And that’s ok. It’s ok to be feeling what you’re feeling now. Frightened. Enraged. Lost.

But know that those feelings will fade, and you’re better than your temporary temperaments. For man is not made for defeat. A man can be destroyed but not defeated. And when you’re ready, there are people standing by to help.

If you do need help, there are some resources in the “Other” section below that might be worth checking out.

And if you’re fortunate enough to be able to help, the “Other” section also highlights ways to do so. It’s ok if you’re not in a position to help right now; “secure your oxygen mask” first.

In these trying times, we’ll be tossed by waves of fear and hopelessness, but will not sink to despair. If we all help rather than harm, we can get through this. Reach out, even if it’s just to one person. You can make a larger difference than you think.

If I can stop one heart from breaking, I shall not live in vain; If I can ease one life the aching, Or cool one pain, Or help one fainting robin Unto his nest again, I shall not live in vain [9]

Shoutouts

- I met with Nick Arkinson of Levatso Holdings, who’s looking to buy a majority stake in a growing company. Companies that fit their model typically have $5M - 20M annual rev, recurring rev model, 15%+ operating margin

- If you’re in Manhattan and need an hourly retail worker, my friend who’s a chocolate expert was laid off

- If you’re in Chicago and need dinner, Ben Arnstein of Kaliflower could use the support

Other resources to help or get helped

- If you’re an hourly worker that was laid off, Sari Azout is donating her ad revenue to people like you. Fill up your info here

- If you’re a startup employee that was laid off, Julia Lipton has a form here that’s matching employees to companies hiring

- If you’re in tech and are looking for a job, Candor has a list showing which companies are still hiring here

- If you’re in NY and want to buy merchandise from restaurants to show support, Eater NY has a list here

- If you want to volunteer for a COVID project, Help with Covid has a list here

Footnotes

- I have a personal bias against yelp due to anecdotes of restaurant complaints

- I believe it’s the difference between a linear (screen once) vs a polynomial (evaluate constantly) function but someone correct me if I’m wrong here

- For example, 95% 5 star ratings and 5% 1 star ratings give an average of 4.8, which feels significantly different from 5 but isn’t really

- Yeah, no prizes for guessing what I’ve been up to in isolation

- Why don’t companies just keep cash, like you and I? Firstly, there’s lack of deposit insurance that will cover balances that large. Secondly, that cash would earn less return. Hence companies enter into repo, treasuries, and other arrangements, in which they exchange their cash for short term liabilities from others. When people think Google has $100bn of cash, that’s true - kinda. It does have that amount in total liquid assets, but only a fraction of it in cash equivalents, and the majority in securities. See their 2019 10K page 50, cash and cash equivalents vs marketable securities

- The book also discusses four types of potential costs from financial crises: 1) deadweight loss from fiscal transfers from taxpayers to institutions, 2) output loss and increase in unemployment, 3) misallocation of resources due to actions taken to ameliorate the crisis, 4) costs to social well being. We can reduce these costs with good policy but cannot eliminate them, and should expect these to occur in every crisis

- Doctor Who

- I was going to write about the trend of niche irl communities that have been gaining popularity this month such as Not Boring Club, Inter Intellect, Get Real etc. Given the situation though I’ll reserve that for later.

- Emily Dickinson

If you liked this, you’ll like my monthly newsletter. Sign up here: