Information speed and investing alpha

This week’s post is commentary on Geoff Yamane’s piece on information speed and investment alpha

investment strategies […] can be re-framed as information front-running: extraordinary returns almost always derive from knowing some truth before others. The viability of these strategies then is related to how fast information travels.

I’m stating the obvious, but to make money you need to sell something for more than you bought it for [1]. Which means you need to have exposure to the investment (long or short) before others do; before the price has corrected to what you believe the true price to be. Which means you knew or believed in something before others did, usually because of some information or analysis you saw.

If winning in investing depends on speedy information, and the speed of information changes, that implies the way to win in investing has to change as well. House of Morgan writes about how company executives and bankers would exchange information all the time, for everyone to make money insider trading ahead of the public. With more stringent regulation [2] that opportunity was removed. Older hedge fund founders talk about how you used to be able to get the news ahead of others, by physically being at the location it was published. With the internet, that opportunity has also disappeared. When information speeds change, investment styles change.

Today’s investment funds broadly seem to have less alpha and this may be due to information moving very quickly

The successful investment strategies in vogue today all seem to be variants of an information-problem.

Many funds today are run by founders who started their investment careers in the 80s, when the previously mentioned edge was largely about getting quality information ahead of others. These funds are still employing that same approach now, despite the difference in information speed. Large funds such as Citadel, Millenium, DE Shaw trade on quarterly earnings releases. It’s plausible that this has caused average returns to be lower [3].

Investment strategies […] seem to be the canary in the coal mine for the declining profitability of many information-dependent business models which derive their profitability from hoarding and exploiting the value of private or expensive-to-access information

Here Geoff generalises the argument to beyond the investment industry. If the edge in investing has declined due to information acceleration, does that mean that other similar industries could be next? He goes on to list life insurance, diamond producers, and chemical producers as examples of industries that profited from hoarding information. If you’re a hoarder, the commoditisation and abundance of information should imply you’re in for a bad time.

Conditions today merely reflect the slow technological commoditization of the different ‘building blocks’ of business: capital, logistics, and now information.

Long businesses that facilitate the flow of information, short businesses whose profits depend on hoarding it

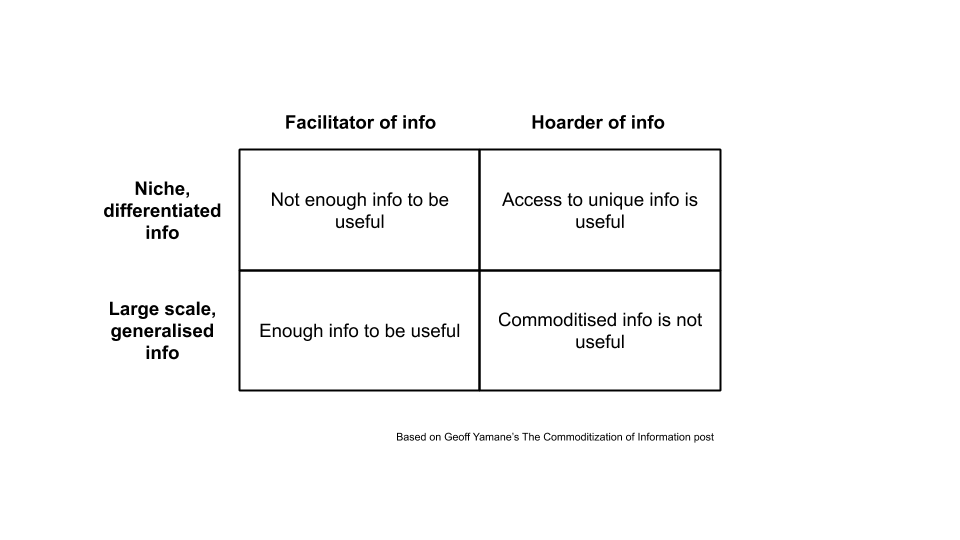

I’m unsure if I’m understanding the argument correctly here, and actually partially disagree. If you facilitate information flow, you need to be a scaled provider in order to win. If you hoard information, you need that information to be niche and differentiated. Newspapers facilitated information flow, but lost out to facebook which had a differentiated resource hoard of its userbase. Mutual funds hoarded their client capital, but lost out to passively managed funds that facilitated client choice of investments at scale. Travel agents facilitated information on a small scale, but lost out to online travel agents like booking.com which aggregated at a larger scale [4].

Thoughts on this are very much work in progress, but something like the below:

In our new informationally abundant world, it seems more difficult for any business or person to hoard and exploit the value of proprietary information. […] What seems to be left for investors are the information problems that don’t scale (hyper-local) and those that do (hyper-scale).

The hyper-local strategies include some forms of mid-market private equity, buying up the ‘un-interesting’ but also undervalued business that others pass on. I’ve seen multiple people talk about doing this, since the market is under-served. There’s no efficient way of getting the deal flow for this [4] and there’s high marginal effort and cost to try this.

The hyper-scale strategy involves some form of software, a virtual good that has effectively zero marginal cost. That could explain all the hype around software copmanies. It doesn’t matter if you make 1 dollar from every user if you have 1 billion users.

Bringing it back to investment styles, what does that mean for fund managers today? In less price efficient markets, you’d want to own niche info, and earn a lot on very little trades. In more price efficient markets, you’d want to facilitate price discovery and earn a little on a lot of trades.

Footnotes

- You could buy low, sell high, or sell high, buy low, but if you keep selling something for less than what you bought it for you’re either money laundering or not going to stay in business very long. Perhaps both.

- See here for a history of insider trading. As far as I can tell, everyone was doing it up till the 80s. Even now, insider trading regulation is still unclear.

- John Huber elaborates on this concept of edge and eroding returns here

- I define hoarding here as when you own the underlying asset, and facilitating when you don’t

- That I know of, but interested in hearing otherwise.

If you liked this, sign up for my monthly finance and tech newsletter