Investing and information

Conviction level: 80%

My own investment framework will forever be a work in progress [1], but one important issue I’ll have to address is the purpose of information in investing, and how to treat new information. I’ve written before about John Huber’s framework for sources of edge in investing, and one of the three edges he cites is informational advantage. Theoretically, if you have more or better information than others, you have an edge in investing and should outperform over time.

A large portion of professional investing time is spent on acquiring information, whether through management meetings, expert network calls, or the entire “alternative data” industry [2]. Trading on insider information has long been a feature problem with markets [3], resulting in various attempts to curb it [4]. So it would seem that people believe information is valuable, and the more of it the better.

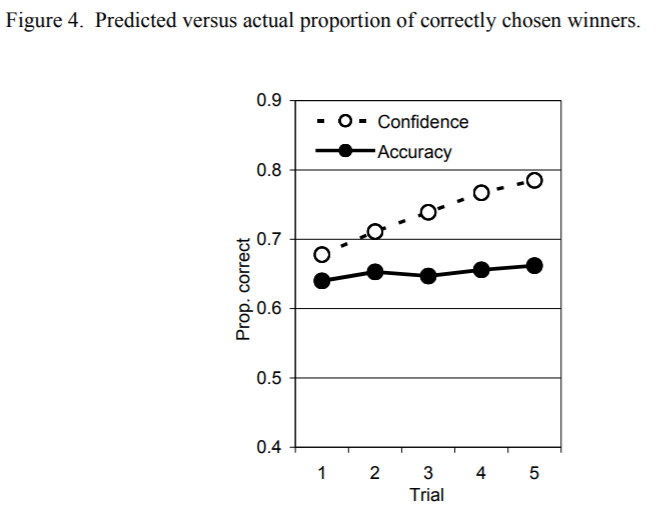

Leaving aside whether you believe you have more information than your competition, does having more information help you make better investment decisions? This post cites studies showing that although individuals have increased confidence with increased information, their accuracy of outcomes doesn’t change:

The Tsai, Klayman, Hastie study with the graph above cites two main reasons for the divergence:

judges show insufficient correction for the effects of cue redundancy as information accumulates. Thus, they tend to overestimate the incremental predictive value of additional information.

Confirmation biases may be another important source of divergence between confidence and accuracy

People think that additional information will be more helpful than it actually is, and also pay more attention to information that supports their beliefs. Very similar to the signal vs noise argument most famously made by Fischer Black [5].

The behavioural investment post goes on to say:

for many investment decisions there are only a handful of information points that are relevant, distinct, and materially impact the probability of a positive outcome. If this is the case, why is there such a desire for more and more information?

And then gives many good reasons for why everyone falls victim to this circumstance [6], such as:

We don’t know what that relevant information is, therefore we include everything we can find.

If a decision goes wrong, we at least want to show that we did a lot of research to support it.

If we make simple decisions based on a narrow range of information we can look lazy, inept and unsophisticated.

And also offers a suggestion of how to overcome this bias:

all investors should think more about what is the most relevant information, rather than concentrate simply on the accumulation of more. For professional investors, a simple idea is to decide which pieces of information they would use if there was a restriction (of say only 5 or 10 items) and then monitor the outcomes of decisions made utilising only these select variables.

As my about page states, I’m also a believer that most information is noise, particularly in investing when the aim is to be better relative to competition, not just better in a vacuum. But of course, incentives in the industry are such that essentially everyone is hunting for lesser known information before it becomes public knowledge. Can you imagine telling a client “oh we don’t pay attention to news or aim to collect more data points as we don’t think it adds value”

One pushback is that “sure, we don’t find helpful information regularly, but when we do, we can size our bet appropriately and this is when we win big”. This assumes that you run a concentrated portfolio then, which would already rule out most money managers [7]. Even then, what makes you sure that you’re not overconfident in this piece of information?

There is definitely information that is helpful and knowable, but this seems the exception rather than the norm. Enron, Worldcom, Tyco etc are famous but there aren’t that many of them. Despite this, I believe the investment industry will continue seeking new information sources to try and get an edge. Whether they actually do or not remains to be seen, though it seems like it’d be difficult as a smaller fund competing against the Citadels of the world with all the data they can buy.

With the above in mind, one part of my WIP investment framework is that I have to want to invest in something even without an information advantage; I have to be ok investing in something with an information disadvantage. It’s unlikely that I’ve found something material that noone else has, and I should always be aware of this bias that makes me overconfident.

Footnotes

- Both a combination of always learning something new and

lazinessthe difficulty in writing all of it out. I am planning to post about it in the future though to refine my thoughts. Just not yet - For example, credit card transactions, app usage data, or search data

- And likely still is, depending on who you talk to and how cynical they are. The general public seems fascinated by high profile cases of suspected insider trading, and beyond the blatantly illegal golf course tip there’s a large grey area of “let’s jump on the phone” interactions that happen daily.

- Current laws are somewhat ambiguous in dealing with insider trading, but as Matt Levine writes, the law is more about theft rather than fairness.

-

Black doesn’t give a precise definition for what noise is, but contrasts it to information in his paper:

In my basic model of financial markets, noise is contrasted with information. People sometimes trade on information in the usual way. They are correct in expecting to make profits from these trades. On the other hand, people sometimes trade on noise as if it were information. If they expect to make profits from noise trading, they are incorrect. However, noise trading is essential to the existence of liquid markets.

- Myself included. Everyone likes to say they focus on the “two or three things that matter” for whatever their work is, but somehow end up paying attention to the tenth thing that happened to show up in a news report on the business

- Most investment firms are rather diversified, for risk, liquidity, or other reasons such as the need to do something. By definition if you’re sizing a position big you can’t have too many of them.