The next machine learning startup is in your front yard

Takeaway

Machine learning is less scary than you think, and more common than you think.

Machine learning magic

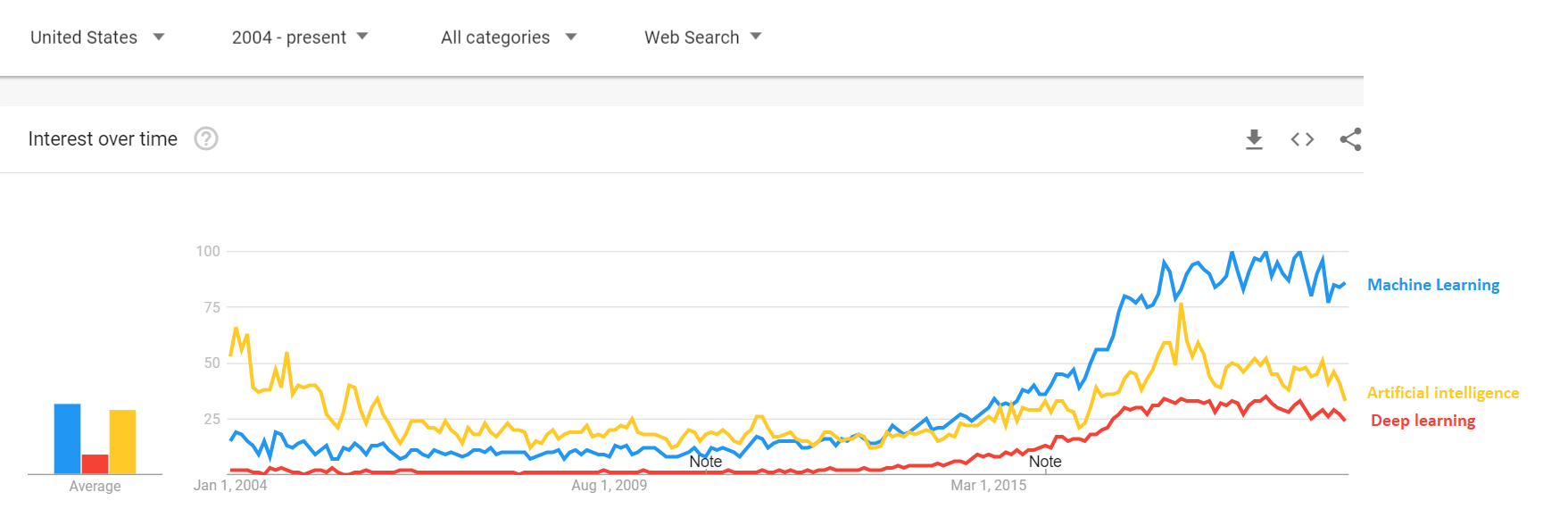

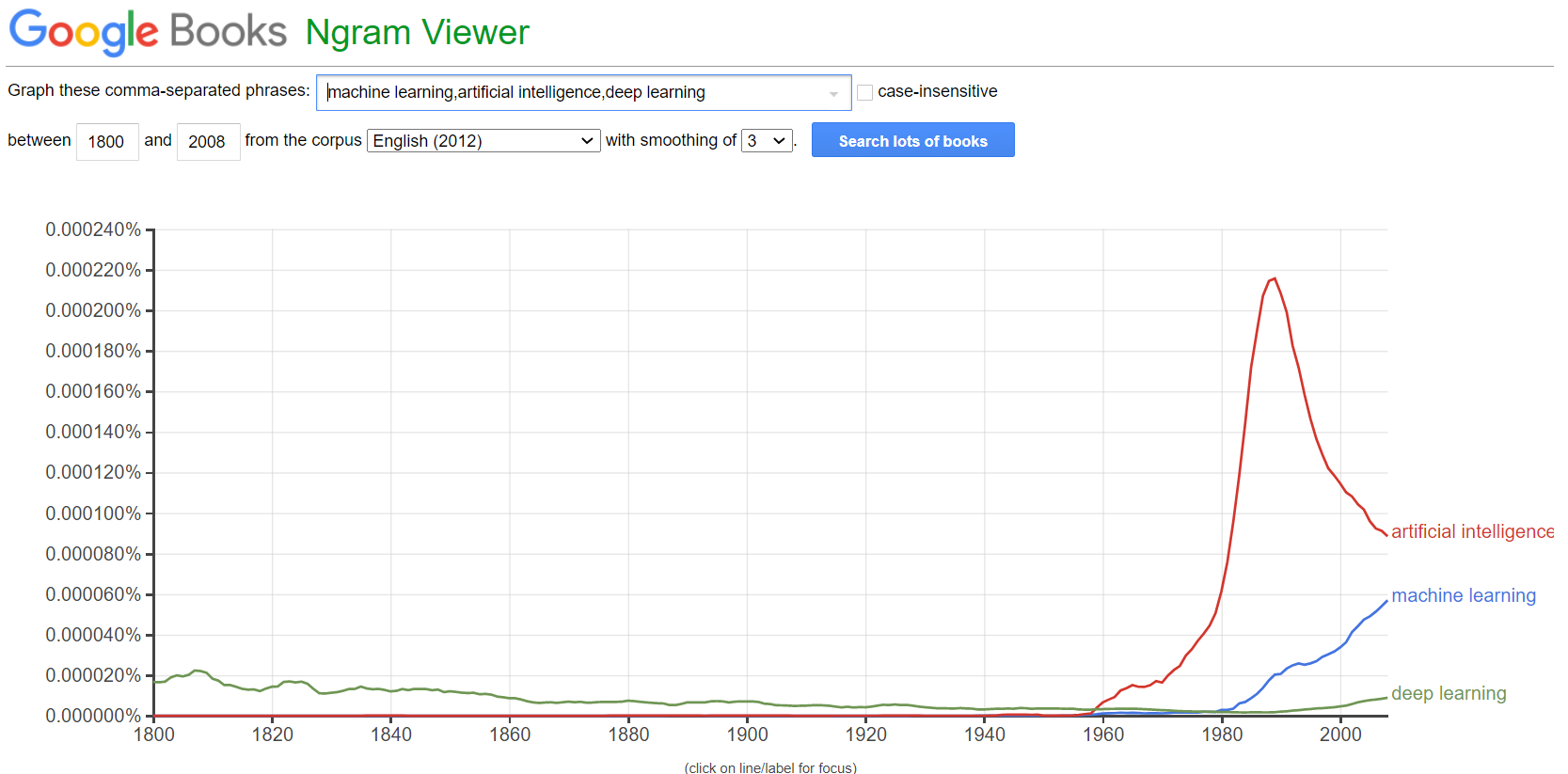

We hear about machine learning (ML), deep learning, or artificial intelligence all the time now [1].

From search interest:

To mentions in books:

To newspaper headlines about robots taking over our jobs:

There’s increased interest in ML, and it seems that every other day there’s a new startup raising $100mm based on their newfangled ML technology.

However, most people are intimidated by ML, equating it to magic that only cutting edge startups do. It doesn’t help that the math can be intimidating:

Today I want to help you get a better intuition of ML, by first looking at a company using ML, and then walking through the basics of how a neural net works. My goal at the end of this is for you to feel less scared whenever someone throws around the term “ML” as though they’re too cool for school.

Machine learning case study

Imagine I came to you looking for investment in a company using ML. Here’s the pitch:

“Company M uses ML and optical character recognition (OCR) to match input data against hundreds of millions of records within fractions of a second. It already has partnerships with Amazon, the US government, and Fedex. Company M has already scaled up to allow >100bn transactions yearly, and has expanded coverage to all of the US.”

Sounds exciting right? I cherry-picked some of the language, but it isn’t too far off from actual press releases by other companies:

“Anyline, a leading startup in Optical Character Recognition (OCR) using AI for text recognition, has raised €10.7 million in Series A funding. The Austrian startup, which is already working with big names like Toyota, IBM, Canon, the UN and PepsiCo, will use the funds to open its first US office in Boston”

But back to company M. The OCR part refers to them looking at an image and recognising what it says via ML. It looks like they do that efficiently, accurately, and at scale. Their partnerships also seem respectable. You probably think they’re a promising unicorn led by Stanford grads who started coding while in diapers.

Would you invest?

If you said yes, you just invested in the United States Postal Service.

No, really, the post office has been using ML for a long time. They started trialing it in 1997, and by 2014 were already mostly recognising addresses via ML algorithms. Not quite the startup stereotype you were imagining.

My point here isn’t to crap on Anyline, or startups similar to it. I’m sure they’re solving difficult problems and are not pure hype [2]. Rather, I want to make you realise that ML is being used in mundane sounding scenarios, and has been for some time now. The next time someone pitches you on ML, keep that in mind.

Machine learning intuition

Now that we know where ML is used, let’s walk through how ML can work. I’ll use a neural network for this, though there are many other ways ML can be run.

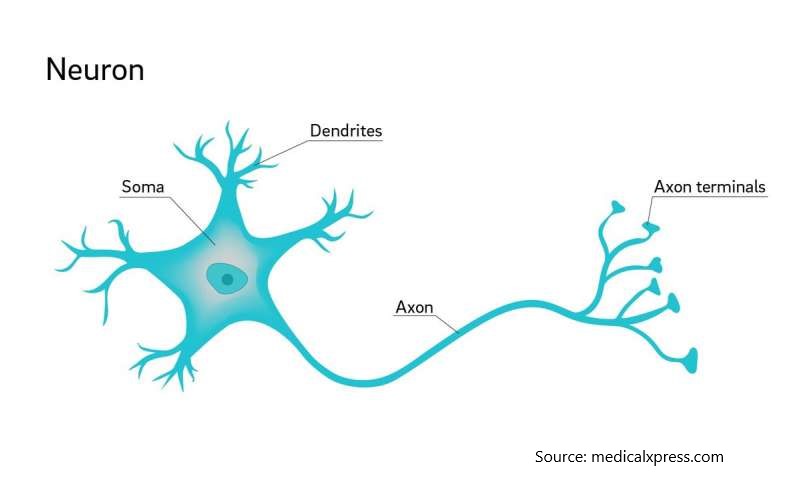

Neural networks are modelled after the brain’s neurons, so it’ll be helpful to get some understanding of how that connection works. Here’s what a neuron looks like:

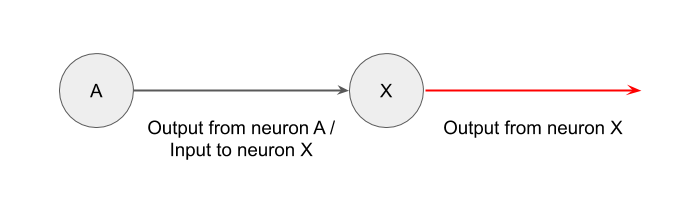

While we still aren’t quite sure how the brain works, a leading theory is that the neurons can take inputs, do some computation, and then send outputs. [3] A simplified way of representing two neurons interacting could be like this. Imagine the circle is the main body, and that line is the axon connecting to other neurons:

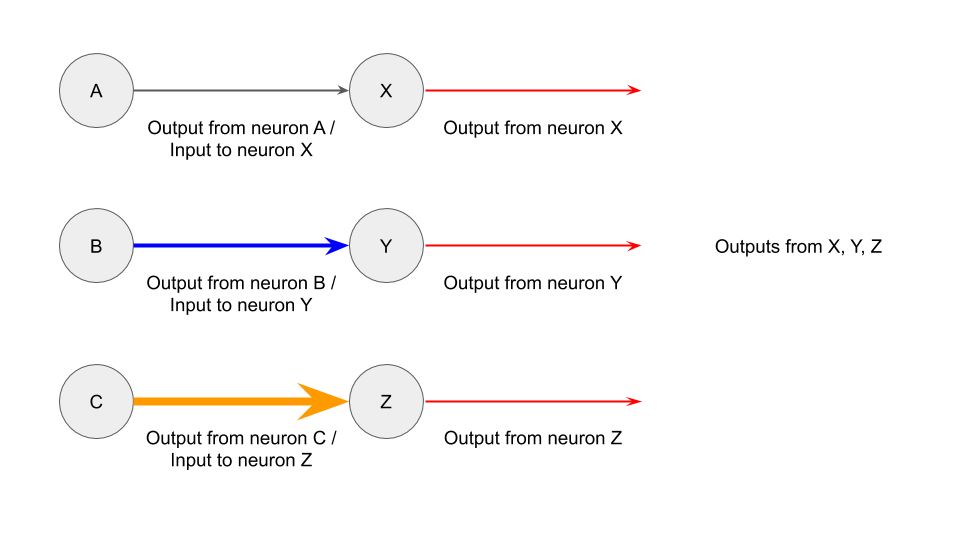

And if you had three pairs of neurons, it could look like this:

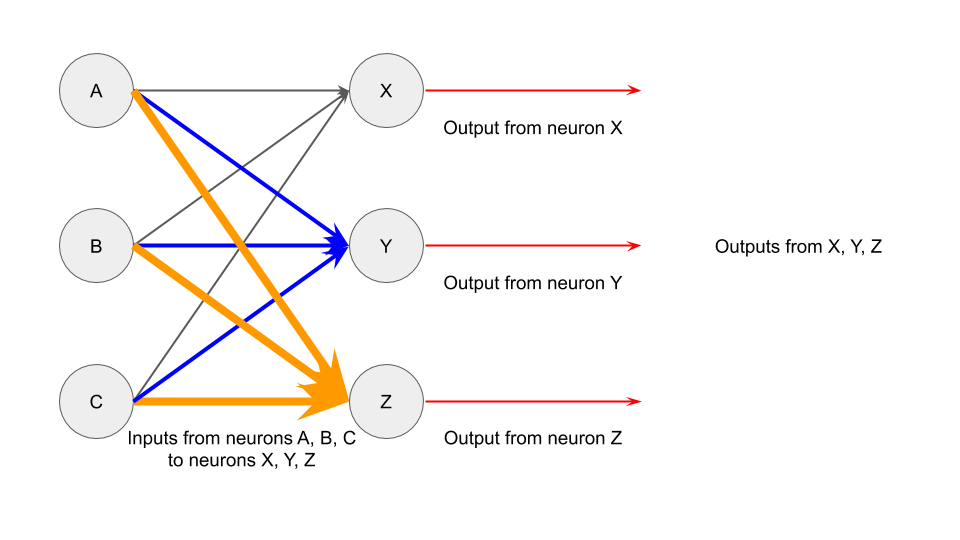

And if the neurons could interact with each other, it could look like this [4]:

Let’s keep that image in mind, as we think about how this might relate to computers and ML.

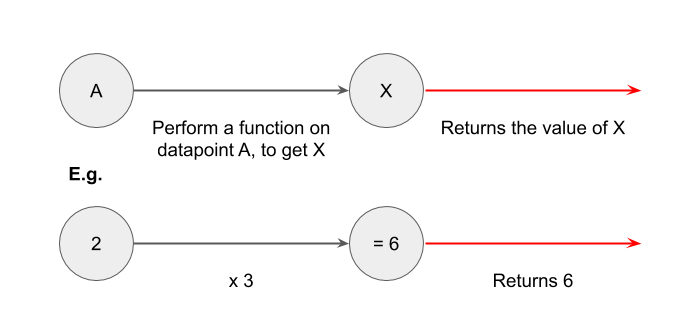

Let’s take a simple math equation, such as 2 x 3 = 6. Let’s set “2” as the input data, “x 3” as the function we want to perform, and “6” as the output data. This gets us something like this:

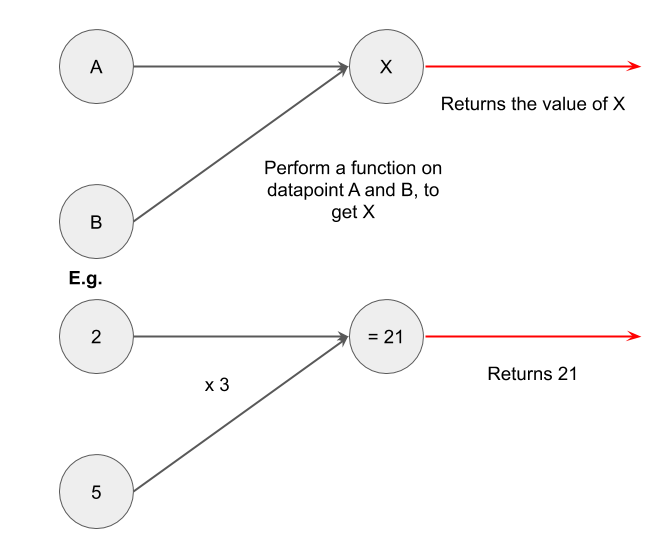

What if you had more than one input data? You could do (2 + 5) x 3 = 21. this gets us something like this:

And once again we can combine multiple functions interacting on multiple inputs, like so:

You can see how this looks the same as the neuron interaction diagram above, hence the name “neural network”.

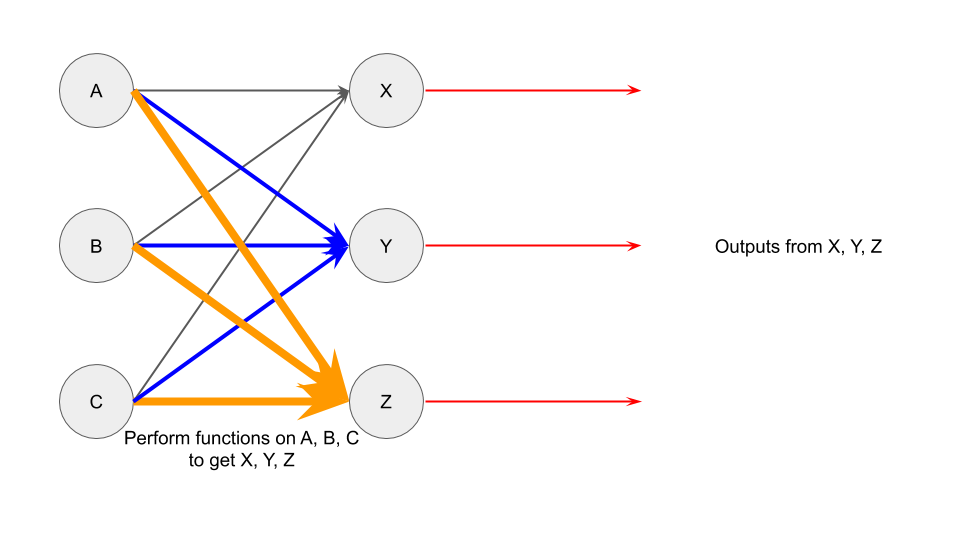

Let’s take it one step further. Imagine you had values in A, B, and C, just like before. This time, the values represent pixel values. In this case, we’re looking at 3 pixels.

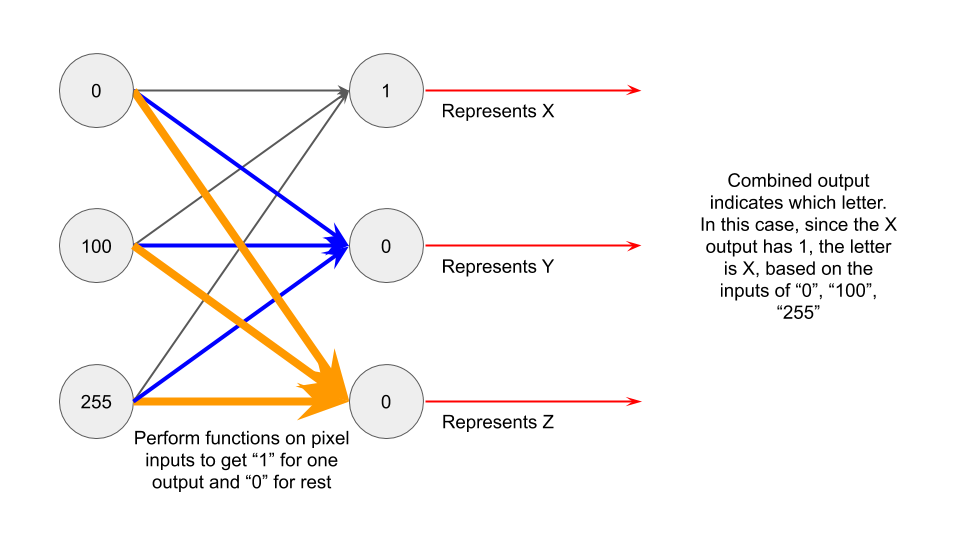

You can similarly do some sort of math function on those data points, and get outputs in X, Y, Z. We’ll ignore exactly what math function we’re using for now [5], but it returns only 0 or 1 from the data points. Not only that, but it also will only give us a single “1”, with the rest being “0”. The outputs here represent the alphabet predicted, if a “1” is returned in that circle.

This looks like:

In this example, we can see that a “1” was returned for the output originally denoted as X. “0” was returned for the other outputs. This tells us that X is the predicted value, based on the inputs from the 3 pixels (0, 100, 255) we gave it.

You can imagine extending such a framework for all letters of the alphabet, and for as many input pixels as you need. The intuition is similar, just that more steps are involved. For example, if you wanted to predict any of the 26 letters based on an image of 1000 pixels, you’d need 1000 inputs on the left, and 26 outputs on the right. Of the outputs, only 1 would have “1” in them, and the rest would be “0”.

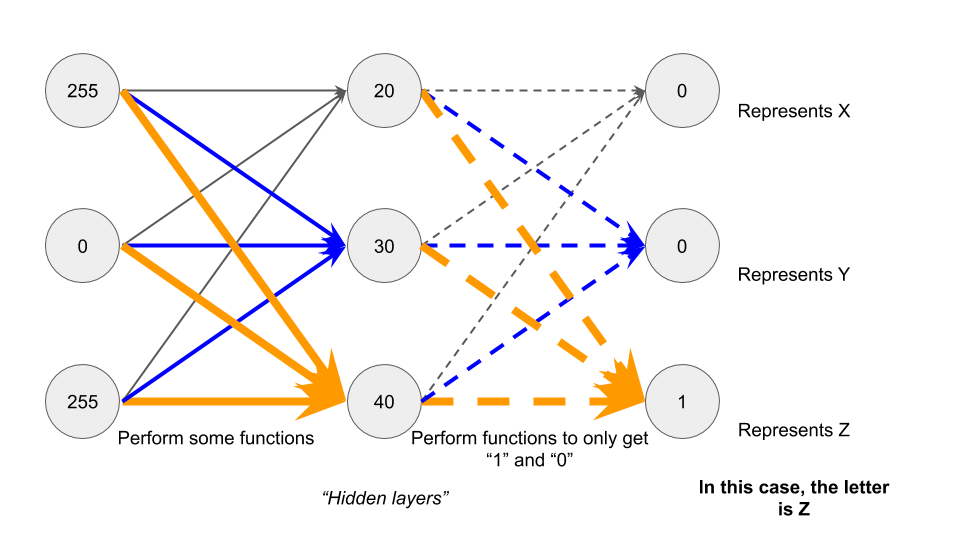

You’re not limited to just two layers of input and output either. You can also include more “hidden layers” that take the input from the left, and then return an output to the right. As long as you set up your functions such that they return “1” and “0” at the last layer, you’re good. There can be any number of hidden layers, and each layer can have any number of elements, not needing to be the same as the input or the output.

And that’s it! You’ve seen how a process can convert data inputs (such as pixel values of images) into outputs (alphabets and addresses). You now understand how most neural networks function. Many ML implementations use neural networks, which means you now also know the underlying concept driving these ML companies.

Of course, the actual setup is more complicated and requires way more time and expertise [6]. I’ve skipped over all of the math, stats, and programming that makes ML actually harder to implement in real life. However, hopefully the intuition that you now have will make you less intimidated whenever someone uses “ML” as a buzzword in the future.

Footnotes

- I’ll use machine learning (ML), deep learning(DL), or artificial intelligence (AI) interchangeably throughout the post, but technically they’re different things, some being a subset of the other. For the sake of the post it doesn’t really matter though.

- Well, some are probably complete cons

- I’m not a scientist, correct me if I’m wrong here.

- I’ve shown all the inputs into one neuron as one colour and size for ease of understanding, especially when translating it to the neural network math. You could think of the groupings in other ways though, such as all the outputs from one neuron as one colour.

- What’s happening here is that there’s a first function performed of the parameters multiplied by the inputs, and then a logistics function applied to range bound the output from 0 to 1. The idea is to train the data repeatedly on the training data set such that the first function of parameters gives you a low prediction error when measured against a validation data set.

- For example, how do you know what function to use? How do you even set this up in a program? How do you check that the predictions are accurate? I’ve simplified most of the technicalities, but if you’re interested in learning more, Andrew Ng’s coursera is a good place to start. Warning that it is much more involved and difficult.