Wisely and slow, they stumble that run fast

Takeaway

The pace layer framework can be used to model civilisations, with each layer moving at its own speed and causing change in others. Forcing layers to change too quickly causes catastrophe.

Houses and civilisations

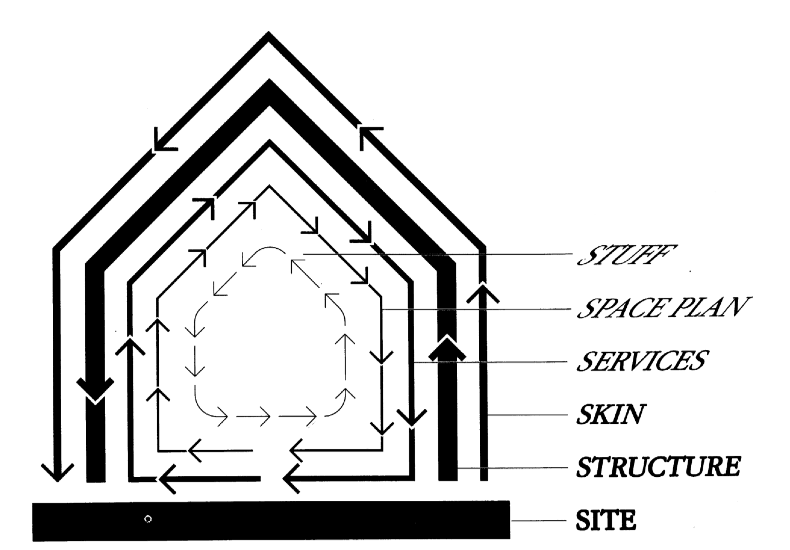

Imagine a building. Perhaps the office you work in, or the house you live in. What parts of that building change over time? How quickly do they change?

The stuff in the rooms change all the time. You buy the new Amazon Echo, you throw away the old lamp. Change is constant and frequent.

The space plan, or interior layout, changes less frequently. Perhaps your office finally puts up a wall between your desk and the bathroom, the day after you leave the company. Or you decide to convert your yard into an arcade. Change here is intermittent and less frequent.

The services within, your plumbing, electricity, gas, and more, change even less frequently. As does the skin, or exterior of the building. Neither of those might change before you move out of the place.

The structure, or skeleton, rarely changes unless part of a renovation or deconstruction.

And the site of the building itself, that geography essentially stays the same.

In 1994, Stewart Brand of the Long Now Foundation proposed the above model as a way to think about how buildings learn and evolve [1]. A building can be thought of as having multiple layers, all changing at different rates. A healthy building will allow for controlled interactions between layers, all moving at their own pace.

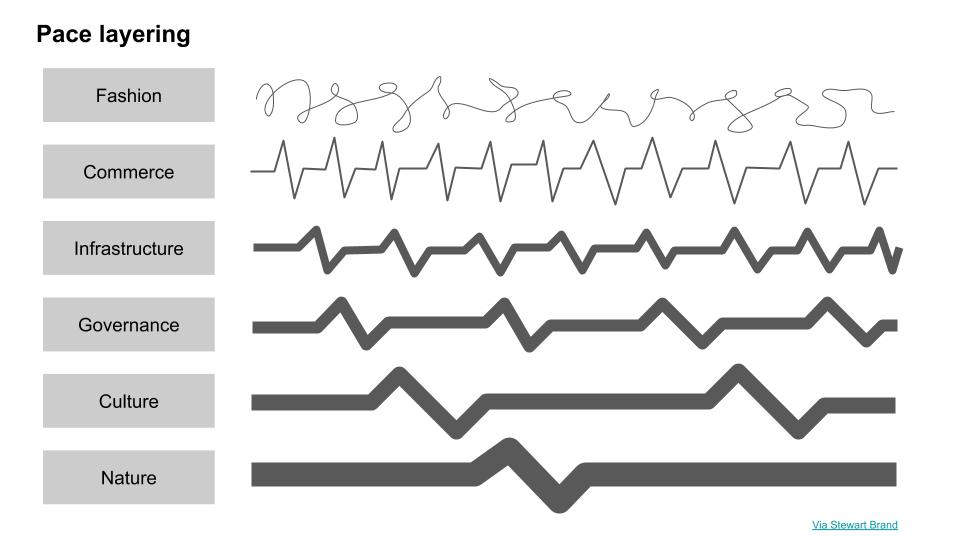

In 1999, Stewart further extended the framework to apply to civilisations. What parts of civilisation change over time? How quickly do they change? How do they interact?

He called this framework pace layering, and proposed “six significant levels of pace and size in the working structure of a robust and adaptable civilization.”

In order of the fastest moving level to the slowest, these levels are:

- Fashion/art

- Commerce

- Infrastructure

- Governance

- Culture

- Nature

Fashion moves quickly, nature moves slowly. Stewart describes how these layers interact:

Fast learns, slow remembers. Fast proposes, slow disposes. Fast is discontinuous, slow is continuous. Fast and small instructs slow and big by accrued innovation and by occasional revolution. Slow and big controls small and fast by constraint and constancy. Fast gets all our attention, slow has all the power.

Change happens across all of the layers, but each at their own pace:

In a durable society, each level is allowed to operate at its own pace, safely sustained by the slower levels below and kept invigorated by the livelier levels above.

I’m assuming the above means that change isn’t bad, and in fact is desirable. A faster moving layer can provide energy to re-energise a slower moving one into a better direction. However, it needs to respect the pace of the slower moving layer:

If commerce, for example, is allowed by governance and culture to push nature at a commercial pace, then all-supporting natural forests, fisheries, and aquifers will be lost.

If governance is changed suddenly instead of gradually, you get the catastrophic French and Russian revolutions.

In the Soviet Union, governance tried to ignore the constraints of culture and nature while forcing a five-year-plan infrastructure pace on commerce and art. Thus cutting itself off from both support and innovation, it was doomed.

The above are all examples of how we shouldn’t push slow layers to move more quickly. A layer has a natural speed [2]. Even if we can do so, we should avoid bringing other layers to the same speed as a faster one.

Is there a case where we shouldn’t push fast layers to move more slowly? Put another way, when do we want to accelerate change in the faster layers of fashion, commerce, or infrastructure? Or should we always aim to reduce our velocity? There doesn’t seem to be a clear answer from the article.

Separately, Stewart points out how “as people get older, their interests tend to migrate to the slower parts of the continuum.” Fashion is less of a concern compared to the culture you want to pass on to your grandkids. This seems true anecdotally, though the research on this seems mixed [3].

Stewart describes how each pace layer affects the other:

Fashion’s frothy energy energises commerce. The latest version of a phone is released, and everyone clamours for it.

Commerce absorbs that shock and influences infrastructure. New wireless tech is deployed to cater to business demand.

Infrastructure often can’t be funded entirely by commerce, and gets governmental support [4]. Governments allocate capital to fund construction of the systems needed to support the new tech.

Governments then craft the culture of a country over time. Their implicit or explicit incentives shape how society should feel about phone usage, ranging from nonchalance to mobile game time restrictions.

Culture then nudges nature. Given the scale of nature though, we need to be careful what we’re disturbing here.

A layer has most direct impact on the ones around it, and then that impact diffuses across the stack. Healthy civilisations allow for layers to change at their own pace, and still evolve over time.

Stewart concludes:

The division of powers among the layers of civilization lets us relax about a few of our worries. We don’t have to deplore technology and business changing rapidly while government controls, cultural mores, and “wisdom” change slowly. That’s their job

Each layer has a natural speed, and we need to work at that speed within the layer. Rushing something will be counterproductive. Wisely and slow, they stumble that run fast.

Again, what I wonder is if there’s ever a case to be made to make change quicker in faster layers. There are historical government controls and cultural mores that we deplore today with the benefit of hindsight. Could we have learnt quicker?

The total effect of the pace layers is that they provide a many-leveled corrective, stabilizing feedback throughout the system. It is precisely in the apparent contradictions between the pace layers that civilization finds its surest health

The layers interact with each other, both reinforcing and destroying at alternate points in time. A healthy civilisation allows for change within and between layers, but doesn’t force all of them to move at the same pace. To do otherwise results in destabilising feedback.

Footnotes

- Full notes for the book How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built can be found here. Stewart is best known for the Whole Earth catalog. Also, I’m a member of the Long Now, and think it’s worth checking out. They do cool stuff.

- Stewart gave time ranges for the building components, but not for the civilisation unfortunately

- Other papers seem to find a small effect or other factors to explain the perception that older people are more conservative.

- Stewart’s point here is that “The payback period for things such as transportation and communication systems is too long for standard investment, so you get government-guaranteed instruments like bonds or government-guaranteed monopolies. Governance and culture have to be willing to take on the huge costs and prolonged disruption of constructing sewer systems, roads, and communication systems, all the while bearing in mind the health of even slower “natural” infrastructure—water, climate, etc.”

If you liked this, sign up for my monthly finance and tech newsletter: