Secrets of Sand Hill Road was worth reading

Takeaway

Secrets of Sand Hill Road was a good read even for someone in finance, less so if you’re in VC.

Secrets of Sand Hill Road book summary

I read Secrets of Sand Hill Road over the holidays and thought it was a decent intro to VC and how the industry is incentivised. As someone not in the industry and only with angel investing, public markets and investment banking experience, I still learnt some things that I hadn’t known before. If you are in the industry I feel like there might not be that much new information, though you’re likely not the target audience. Highlights from the book below:

the “something more” that Marc and Ben decided to build a16z around was a network of people and institutions that could improve the prospects for founding product CEOs to become world-class CEOs

Recognising that capital could become a commodity and needing to differentiate via other means.

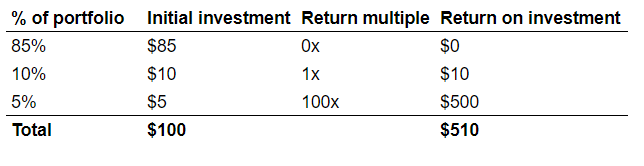

For most VCs, the distribution of [returns] looks something like this:

50% of the investments are “impaired”, which is a very polite way of saying they lose some or all of their investment

20-30% of the investments are “singles” or “double”. You didn’t lose all the money, but instead you made a return of a few times your investment

10-20% of the investments are our home runs, where the VC is expecting to return ten to one hundred times her money

Scott’s mentioned this publicly before but always helpful to get a reminder of what the base rates are for VC. I’ve written more on the subject before

As a reminder, even if you’re more conservative on the distribution of returns than above, those 100x returns will still give you success:

How do you evaluate a founding team? Different VCs of course do things differently, but there are a few common areas of investigation:

Why back this founder against this problem set versus waiting to see who else might come along with a better organic understanding of the problem?

Can I conceive of a team better equipped to address the market needs that might walk through our doors tomorrow?

The founders leadership abilities

Ideas are not proprietary, nor likely to determine success or failure in startup companies. Execution ultimately matters, and execution derives from a team’s members being able to work in concert with one another toward a clearly articulated vision.

The last point bears repeating. As Marc Andreessen pointed out in this talk, many ideas have historical precedent, but didn’t work for some reason or other. Thinking of ideas is easy, getting good ideas is hard, and hacking them to work even harder.

Sins of omission are worse than sins of commission

Given the power law dynamics discussed above when talking about VC returns, this is unsurprising. VC stakes in any individual company are small enough that they should aim to diversify.

[As a founder], you should ask about the specific fund from which the VC is proposing to invest in your company […] The later in a fund cycle your investment occurs, the greater the likelihood that the VC may also not have sufficient reserves to set aside for subsequent financing rounds

The later in the fund cycle, the more likely money has been reserved for follow ons of other companies before you, and the less likely you’ll get your shot.

most GPs contribute 1 percent of the fund’s capital, and many times they will contribute 2-5 percent of the capital

Helpful to know industry benchmarks

If GPs invest in pass-through entities, they can [create a] potential tax risk for LPs; investing in C corps raises no such issues. Thus, most GPS will avoid investing in pass-throughs as much as possible.

I always have to look up the differences in tax treatments for various company structures; this is a good reminder of a key reason to structure as a C corp

[15 percent] does tend to be the standard size of an initial employee option pool in a startup

Again, helpful to know industry benchmarks. See Fred Wilson here or Matt Cooper here for more details on option pools and how to value your options

you should be able to credibly convince yourself that the market opportunity for your business is sufficiently large to be able to genreate a profitable, high-growth, several-hundred-million-dollar-revenue business over a seven-to-ten-year period

Not all businesses benefit from venture capital, given the power law return seeking that we discussed earlier. **That doesn’t make it a bad business, just one not suited for VC. **

Some companies run balance sheets that are light on debt, others run heavy on debt. Does that make one inherently better than the other? You might lower your cost of capital taking on more debt, but if it’s unsuitable for your business you’ll still end up in trouble. In the end it’s about taking on the appropriate type of capital for you.

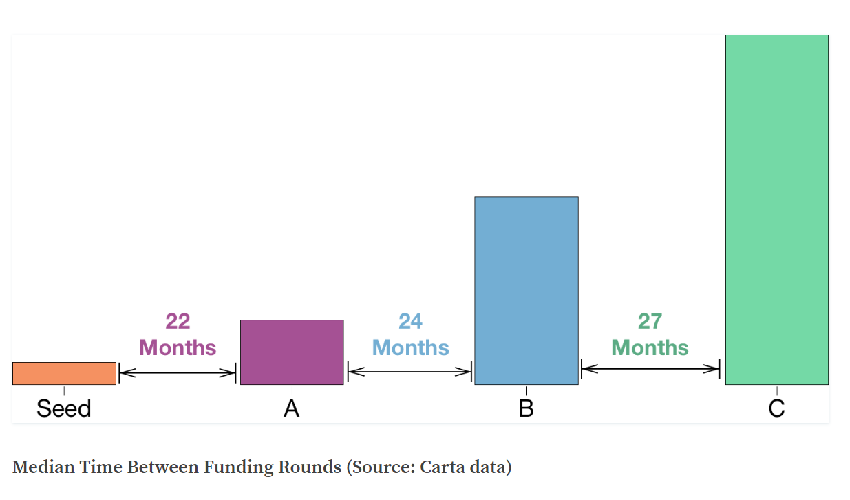

most entrepreneurs at the early stages of their business raise new capital every twelve to twenty-four months

Carta and Crunchbase show fairly similar time periods as well.

One big mistake we at a16z have seen entrepreneurs make is to raise too small an amount of money at an aggressive valuation, which is precisely the thing you don’t want to do. This establishes the high-watermark valuation, but without the financial resources to be able to achieve the business goals required to safely raise your next round well above the current round’s valuation.

This is why I am skeptical whenever aggressive early stage valuations are announced in the news. Without more context, it’s hard to tell whether that was a good or bad thing for the founders. Often you really only know years down the road or even later. The formative example for recent times would be WeWork.

if you are pitching a VC and she suggests that your go-to-market plans are all wrong and should instead be done differently from how you have pitched, the wrong reaction is to immediately abandon your plan

a fact pattern we see very often at the time of a Series A financing is that the entrepreneur is surprised to learn that she has sold much more of the equity than she anticipated through a series of these convertible notes.

I’m preferential to priced rounds, but that’s not the current state of the market, as Fred Wilson has written about. Priced rounds make cap tables clear to founders, but kicking the can down the road is easier to do, hence the proliferation of ambiguity. A compromise is to make the cap table clear even when you’re doing SAFE and other converts, but for some reason people, founders included, seem reluctant to do that.

So what do VCs actually do to value early-stage startups?

what does the company need to look like in five to ten years to be a meaningful return driver, or winner, for its fund?

what would have to go right with the business for that to happen? Is the market size they are going after big enough to support a company with $100mm in revenue? What are all the things that could cause the company to fail? How do I assess the probability of each of these nodes on the decision tree toward success or failure?

Given the early stage of the company, financials are usually less relevant. But if you can’t tell a story of how you can become a 10-100x return, you probably won’t be an attractive candidate for investment

a greater than 1x liquidation preference can be a way of aligning interest more closely among investors (and employees) who have a much lower entry valuation into the company with those who are just entering the company for the first time at a significantly higher valuation

“nonparticipating” means that the VC doesn’t get to double dip. Rather, she gets a choice: take her liquidation preference off the top or convert her preferred shares into common […] “Participating” is the opposite flavour - not only does the VC get her liquidation preference first (her original investment back), but then she also gets to convert her shares into common and participate in any leftover proceeds

Would be interested to know the percentage of deals at all stages that have participating preferreds.

there are pros and cons to every deal, and there usually is no definitive right answer. Some of the decision depends on how confident you are in the company’s future, how much money you really need now to accomplish your goals, and how much you are willing to gamble on the downside in order to give yourself more upside

Similar to the point I mentioned above about no “platonic ideal” capital structure, just the right one for you

board members do not owe fiduciary duties to the preferred stock. Instead, the courts have long said that preferred rights are purely contractual in nature

I hadn’t realised this before

If you lose a duty of care case, that’s certainly no fun, but at least you won’t have personal liability for the ultimate damages. Not so with violations of duties of loyalty

Hadn’t realised this either. This was in relation to legal liability for investors and founders.

In the absence of [doing a down round], the company may continue to move forward but is likely to face another challenge when seeking to raise its next round of financing […] And nothing can be more damaging to a business than having to reset once again after it is just starting to regain some of its momentum

Notice the trend of how deferring something painful (pricing a round rather than leaving it ambiguous) usually just leads to bigger problems down the road.

For a16z, investing in a team of post-investment resources is one way in which the firm hopes to compete among a group of other very successful and competitive venture firms.

You’re starting to see this value add spread among the VC community, from First Round’s Talent network to NFX’s content library. This comes full circle with the network of people idea that a16z was founded with.

First, many of the traditional venture capital firms have increased their fund sizes to be able not only to fund startups in the very early stages, but also to be a source of growth capital throughout their life cycles.

Second, as companies have elected to stay private longer, more nontraditional sources of growth capital have entered the financing market. Whereas public mutual funds, hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, family offices, and other strategic sources of capital had traditionally waited for startups to go public before they would invest growth capital, nearly all these players have now made the decision to invest directly in later-stage startups

Examples include traditionally fundamental long/short tiger cubs such as Coatue or Tiger Global now having well developed private arms that might be even more successful than their public arms.

If you liked this, sign up for my monthly finance and tech newsletter: